☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

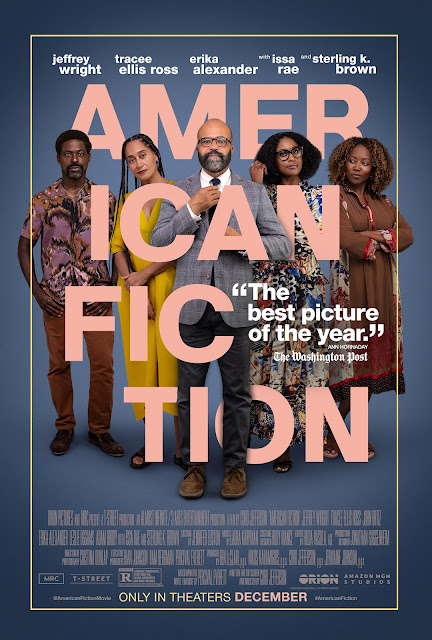

American Fiction (2023) – C. Jefferson

Audacious directorial debut by Cord Jefferson who also

won the 2024 best screenplay Oscar for adapting Percival Everett’s book

Erasure. Apparently, the title of the

film was going to be the same as the title of the book by Stagg R. Lee in the

film but ironically the producers must have gotten cold feet. Irony is the name of the game here in this

smart dramedy that manages to retain its heart, make some solid points, and

even go “meta” at the end while never losing the audience. It is great to see

Jeffrey Wright (as Thelonious “Monk” Ellison) take the lead (as he did so many

moons ago as Basquiat) and he holds down the centre of the picture with a not-always-likeable

character who nevertheless is very human.

He’s a respected writer (and college prof) who doesn’t have sales to match

the esteem. After seeing another Black writer

receive plaudits for writing a trashy novel of the (stereotyped) Black

experience, he bangs out what he thinks is a parody and gives it to his

agent. This sociological theme sits

alongside a nicely delivered family drama, given life by Wright, Leslie Uggams,

Sterling K. Brown, Tracee Ellis Ross, and Myra Lucretia Taylor. Erika Alexander

is excellent as Monk’s love interest, an independent woman rather than a

sidekick. Endings to films like this are

often hard to stick so kudos to the filmmakers for taking chances and landing the

perfect one (or two… or three).

.jpeg)