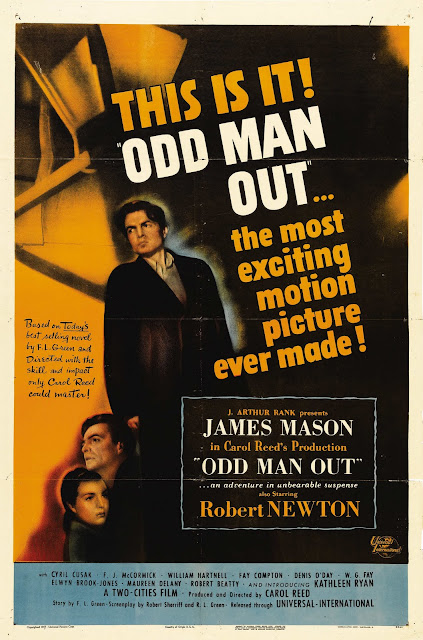

☆ ☆ ☆ ☆ ½

Odd Man Out (1947) – C. Reed

One of the first DVDs I ever bought, but it has been

ages since I watched it. James Mason

stars as one of the leaders of the IRA in Belfast, Johnny McQueen, who has been

hiding out after escaping from prison but is now planning a payroll robbery in

order to finance their operations. Yet from the start things don’t go right – Mason

plays McQueen as tentative and uncertain and director Carol Reed (later famous

for The Third Man, 1949) uses expressionistic touches to show McQueen’s

wooziness as he gets into the car to head to the job. Of course, the subsequent heist suffers as a

consequence and McQueen kills an innocent employee during the escape while also

being shot himself. He then falls backwards out of the getaway car, with his panicked

partners leaving him passed out in the road.

From there, the movie depicts McQueen’s journey through the snowy night

in Belfast, encountering numerous supposed loyalists and other friendly souls,

none of whom assist him enough to help him back to safety. At the same time,

McQueen experiences delirious hallucinations, as he is both dying and coming to

terms with his crimes. There is a burning spiritual fever in Johnny as he

attempts to avoid the police dragnet – but to what end? Kathleen Ryan is in

love with Johnny and wants to rescue him, but neither she nor anyone else can

see a way forward beyond Johnny’s pre-ordained fate. Reed and cinematographer

Robert Krasker shot the film as a blend of postwar neo-realism (the slums of

Belfast), film noir (the chiaroscuro lighting and dark themes), and expressionism

(McQueen’s visions distort reality). To me, the film seems to share structure

and themes with Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man (1995), which also follows a man on a

journey from life to death, offering a critique of society on the way. In both

films, humans struggle with difficult moral decisions where right and wrong can

confusingly depend on the eye of the beholder. Yet, at the end of the day, as the police

inspector hunting Johnny succinctly states, for him, there is neither bad nor

good, only innocence and guilt.

.jpeg)