☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

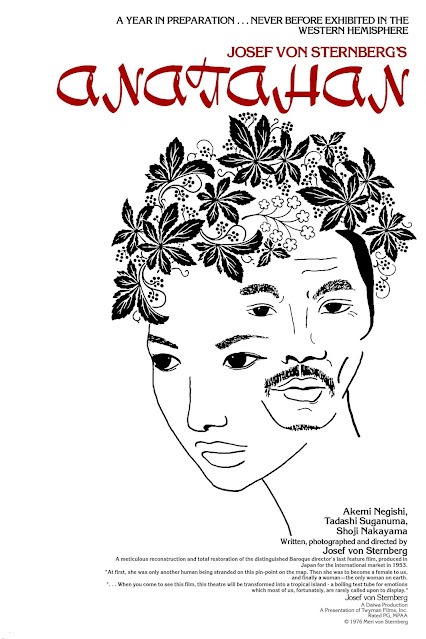

Anatahan (1953) – J. von Sternberg

I believe it is only a coincidence that I’ve watched

two movies featuring people stranded on deserted islands this month. First,

Lord of the Flies (1963) and now Anatahan (1953). Although similar in the

predicament of the protagonists (young boys after a plane crash vs. Japanese

soldiers after their boat sank) and in their inevitable descent from civilized

to instinctual, the films otherwise are very different. Brook’s film strove for

realism with the boys actually filmed in Puerto Rico on real beaches and in the

tropical jungle whereas Anatahan, which was Josef von Sternberg’s final film,

is as artificial as they come but stunningly so. In his earlier career, with

Marlene Dietrich as his muse, Sternberg was already a master of cinematography,

working with light and sets in an Expressionistic way. Anatahan was filmed

decades later on a soundstage in Kyoto with nary a beach or jungle in sight;

instead, foliage was constructed from paper and cellophane with the

Kabuki-trained actors front-and-center in the clearly unreal settings, dappled

with light and shadow. Even weirder,

Sternberg does not translate any of the Japanese spoken dialogue but provides a

voice-over narrative (in his own voice) that describes the action, often

offering asides and commentary, as if from the perspective of one of the

characters. (In one episode, he remarks that we are seeing scenes that he

couldn’t possibly have witnessed face-to-face so viewers are cautioned about

their veracity!). Whereas the boys in Lord of the Flies descend into “survival

of the fittest” tribal warfare, in Anatahan, when the stranded men discover

that they are not alone but share the island with an abandoned plantation owner

and his “wife”, Keiko (Akemi Negishi), their military discipline collapses into

sexual desire and jealousy. When a downed plane is discovered with two pistols

inside, the guns transform the power dynamics of the erstwhile community to allow

certain men to act on their desires. The events of Anatahan are based on a real

story – the stranded Japanese soldiers remained on the island for 7 years, long

after WWII had finished, and refused to believe American messages sent to them

declaring the war over and instructing them to return to Japan. They really

fought over a woman and a number of men really died. At one point, von

Sternberg inserts actual stock footage showing real Japanese soldiers returning

to their country in defeat after the war, a heartrending moment that stands

outside the film but calls attention to the motivated denial of the soldiers in

the story. Von Sternberg may have concocted the idea that these men were distracting

themselves from this harsh reality with coconut wine and sexual fantasies but

the Brechtian effects of the artificial sets and unusual narrative allow the

viewer greater latitude to contemplate the social and psychological

significance of the action. But if you just want to watch it for its dazzling and

strange beauty (and eroticism), go ahead!

No comments:

Post a Comment